My ex-boyfriend, a New Jersey Corrections officer, told me months ago about a raid at his jail. He and other fellow officers wore latex gloves and searched all crevices to confiscate cell phones, cigarettes, drugs, nude pictures of women or children and other contraband.

A decade ago, I was stashing a different kind of contraband: gum, chocolate-flavored laxatives, diuretics, diet pills, anti-depressants and salt packets. Though I’ve never been in jail, I felt imprisoned by the pink walls and watchful eyes of nurses and mental health workers at the now-defunct Eating Disorders Unit at St. Claire’s Hospital in Boonton , N.J.

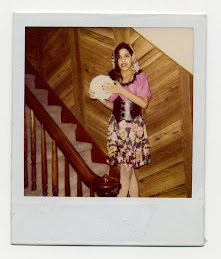

As a Cuban American where I grew up believing food is love, my parents were baffled by my weight loss. At 13, and 5’3,” I had gone from a healthy 105 pounds to a bony 60 pounds in eight months, carefully hiding my skeletal frame in baggy clothing. My parents bribed me to eat my favorites: rice and black beans and caramel custard, but I refused. When my curly brown hair started falling in chucks and two of my molars broke off, they rushed me to gastroenterologists, pediatricians and even oncologists: they’d sooner believe I had cancer than an “eating disorder.” Finally realizing I was anorexic, they took me to a hospital that specialized in eating disorder treatment.

Once at the hospital, I was scared of gaining weight and losing the false sense of control starving had given me. Though I knew how to cut calories and exercise for hours at a time, I learned how to hide my Prozac or give it away, how to barter for gum and salt packets, and how to appear as if I’ve gained or maintained a certain weight from different patients at the hospital.

During my first week at the Eating Disorders Unit in March 1997, my roommate Christine told me that chewing cinnamon gum burned more calories and that I should sit next to the bulimics and sneak them some of my food under the table. Christine had long reddish brown hair and pale skin, and looked more like she was 13 than 17. She had been in and out of hospitals for the past four years.

Since our meals were supervised, patients weren’t allowed to have any food in our rooms. We also weren’t allowed to have plastic bags for fear bulimics would throw up and hide the vomit in their rooms. But when some of the “healthier” patients were given privileges like day-long “passes” to leave the hospital, some would stash gum and laxatives in their socks, bra, or other articles of clothing to bring back to the in-patients. Other times, outpatients would bring the contraband: carefully hiding it in unsearched crevices in their backpacks or shoes. Some of us would get creative during dinner time, snatching the salt, pepper and sugar packets that were brought to us with our food trays.

I usually traded gum for salt packets, so I could retain weight for the following morning’s “weigh in.” During my second stay as an inpatient at that hospital in July 1997, I had become adept at the bartering business. Though alliances between anorexics and bulimics were rare, Lisa, a 33-year-old bulimic with rotted teeth, called a meeting with all 11 inpatients to exchange contraband and war stories.

“Does anyone have Klonopin? I’m really jittery and need a fix,” said Lisa, who boasted her bulimia started on September 27, 1981, the first time she struck her fingers down her throat.

“I have one,” said another patient who was prescribed the panic disorder medication.

I spit out my Prozac from under my tongue and placed it under an air vent.

“Who has gum? I have salt packets and a diet pill, if anyone wants,” I said.

Patty, a 25-year-old exercise-obsessed bulimic/anorexic was pacing around the room. The youngest, Amanda, 12, stayed quiet.

She told me know she only bartered her anti-anxiety medication when she left St. Claire's for Cornell University Medical Hospital, where patients with eating disorders were locked away with people with schizophrenia and those who chose treatment over jail.

"At St. Claire's it was just a game. I wouldn't eat because I didn't like the staff there. It was like my rebellion," said Amanda, now 22.

Throughout Amanda's stay at St. Claire's, she would not eat or drink, getting her nourishment only from the feeding tube - a think plastic tube that goes from your nose to your stomach. I also had “the tube” – that like intravenous provided nutrients from whatever calories we didn’t eat. After the pills and foodstuffs were exchanged, some of us quickly left Lisa’s room. If the nurses or mental health workers suspected a swap, they could put us on “lock down,” asking us to stay in a common area as they put latex gloves and searched every room.

When I began cutting down on cookies and other fattening sweets, I never suspected ending up in a hospital, feeling like a criminal in my early teens. I spent most of 1997 - including my favorite holidays, Easter, my birthday in May, July 4th, Thanksgiving Christmas and New Year’s. Every time I would be discharged, I would go back. The other patients and I would joke about that, since I would only go home for two-week intervals and that was my “vacation.”

My turning point came at 17, when after years of inpatient and outpatient therapy, I grew tired of the revolving door between my house and the hospital. When I was determined to get healthier, I no longer hid food and over exercised. I also took my medication as prescribed. After meeting men and women who’ve quit law school, jeopardized their relationships, had miscarriages and lost jobs, I knew life was more than about counting calories and bartering with bulimics.

“Wow, I never thought of gum as contraband,” said a wide-eyed, Ted, the corrections officer.

“Yes,” I said half jokingly, “I guess you could say you’re dating a former criminal.”